https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5564-3634

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5564-3634ISSN electrónico: 2172-9077

DOI: https://doi.org/10.14201/fjc-v22-24142

“We are what we hear”: metaphors in contemporary Spanish and English commercial hits

“Somos lo que oímos”: metáforas en éxitos comerciales en español e inglés contemporáneos

Mariló CAMACHO DÍAZ

Personal Investigador en Formación Universidad de HUELVA, España

E-mail: mariadolores.camacho138@alu.uhu.es

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5564-3634

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5564-3634

Dra. Mª Carmen FONSECA MORA

Catedrática por la Universidad de Huelva

E-mail: fonseca@uhu.es

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2404-3553

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2404-3553

Fecha de recepción del artículo: 29/09/2020

Fecha de aceptación definitiva: 21/10/2020

ABSTRACT

The subliminal messages transmitted by means of metaphors in songs could influence the development of critical thinking among our youngsters which will reflect on their personality later in life. The aim of this article is to analyse the discourse of the most popular commercial songs in English and Spanish of song-writers and the values they convey to metaphorical compositions. 452 metaphors were identified which have been analysed according to six high frequency themes: love, sexuality, happiness, ambition, madness and violence. The results of the discourse analysis indicate how metaphors are culture-bound and reinforce the idea of a distinct and varied perspective of life on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. Based on the tendencies of composition of these commercial rhythms, results show that metaphors, being sexually provocative and socially controversial, are used as a strong marketing strategy to which our youngsters are constantly exposed to.

Keywords: Contemporary commercial songs; discourse analysis; culture-bound metaphors; perspective of life; values

RESUMEN

Los mensajes subliminales que transmiten las metáforas en las canciones pueden influir en la formación del pensamiento crítico de nuestros jóvenes que posteriormente se verá reflejado en su personalidad. El objetivo de este artículo es analizar el discurso de los compositores de canciones comerciales contemporáneas, y ver qué valores les inculcan a las metáforas. Se han identificado 452 composiciones metafóricas en las canciones más populares tanto en español como en inglés, las cuáles han sido analizadas siguiendo el parámetro de los seis temas más recurrentes: amor, sexualidad, felicidad, ambición, locura y violencia. Los resultados del análisis del discurso indican que las metáforas son culturales y refuerza la idea de diferentes corrientes de pensamiento a ambos lados del Atlántico. Asimismo, muestran que componer canciones sexualmente provocativas y socialmente controvertidas es una estrategia de marketing que funciona; por lo que nuestros jóvenes están constantemente expuestos a estos tipos de mensajes.

Palabras clave: Canciones comerciales; análisis del discurso; metáforas culturales; corrientes de pensamiento; valores

1. Introduction

When communicating, humans show their intentions and express emotions because it is the very nature of the act of communicating itself. Communication is often framed under transnational contexts (Márquez-Reiter & Hidalgo-Downing, 2020) as in the case of pop songs where the audience may get the influence of certain cultural aspects not seen in their native culture. These cultural aspects and emotions are encapsulated into expressions that, depending on the contexts in which they are used, will become metaphorical (Hidalgo-Downing, 2020).

This was already reported by the ancient Greeks. For instance, the rhapsodes narrated epic battles to the common people via a constant rhythm set with a stick, while metaphors were used to communicate emotions, to convince and to persuade and to adorn their literary texts. Socrates (5th century BC) and later, Plato (5th century BC) considered metaphors useful as a strong argumentative instrument in speeches to convince and to persuade the audience. Aristotle, in the 4th century BC (1920), in his Ars Poetics defined metaphors as a linguistic tool to embellish literature, changing the course of use of the figurative expressions in the Greek World: “Metaphor consists in giving the thing a name that belongs to something else […] As old age (D) is to life (C), so is evening (B) to day (A)” (pp. 71-73). Ever since, consciously or unconsciously, humans have used metaphorical expressions as rhetorical devices (Musolff, 2012) to express their feelings, and they also became essential in song-writing in order to seek an effect on the audience.

Lakoff and Johnson (1980), in their seminal work Metaphors We Live By, stated that metaphors are pervasive in everyday life, not only in language, but in thought and action. They opened a can of worms that focuses on this human necessity to express emotions because words do not always have the power of reflecting the intensity or broad picture that metaphors reflect. What is more, metaphors have an impact on social practices prompting small changes in society at a time (Hidalgo-Downing, 2020).

Metaphors seem to be present in any kind of discourse. For instance, Sal Paz (2009) studies metaphors as a lexical construction resource on the Internet to define new technological concepts: World Wide Web (WWW) is a metaphorical analogy to a spider web, except virtually. Kovecses (2010) analysed the metaphors used in American newspapers framing it according to selected criteria and focusing on pattern repetition; just like we focus on the most elaborated examples with great doses of creativity, combining language and music which elicit almost always a flurry of metaphors (Chen, Gibbs & Okonsky, 2020), to shed light with regard to the social implications of the contexts of the songs which does imply a differentiation of musical corpus used leading to two types of audience. Caballero (2014) evidenced that metaphors are vital to understand architecture, where figurative expressions are used on an everyday basis to comprehend the layout of constructions and buildings, for example, a structure or design that resembles a seahorse. And Castaño (2020) relates metaphors with dementia, describing how patients affected by this terrible disease face their actual reality in terms of figurative expressions that help them to express their feelings: “Every day is a battle”. All in all, metaphors are described as powerful linguistic tools to express feelings and ideological perspectives.

Our study examines the metaphors used in a highly frequent discourse: commercial hits. Sánchez and Fonseca-Mora (2019) analysed the video-clip consumption of Slovak university students studying Spanish as a foreign language and found out that the 69% of this population reported on their habitual consumption of musical video-clips sung in Spanish. Illescas (2015) studied the influence of the video clips of contemporary commercial hits in our Western society and concluded that international video-clips were very highly consumed and that therefore, pop stars with their video-clips influence powerfully the values and ideology of our youngsters.

However, metaphors in contemporary musical compositions have not been studied deeply enough. In Manabe’s words “While the individual musical style of many classical composers has been thoroughly studied, analytical studies of the musical idiolects of popular musicians have been relatively rare” (2006, p. 3). This is also the understanding of Hidalgo-Downing & Filardo-Llamas (2020) who analysed the metaphors used in three songs of U2 to describe the situation in Northern Ireland regarding political conflicts of a recent past era. The main aim of our study is to analyse the metaphors used in the lyrics of commercial hits to observe the topics our youngsters are exposed to. As Hidalgo-Downing & Filardo-Llamas (2020) stated, “Metaphors in songs, (…), play crucial roles both in the shaping of ideologies and in the potential to evoke emotions and action in audiences” (pp.71-72), we think that the lyrics of hits could influence the very nature of our youngsters creating a bond that moulds society.

The research on metaphors in song lyrics has normally focused on a particular musical style like tango (García-Olivares, 2007) or on an artist as, for instance, Shakira, a well-known international artist who sings in English and Spanish. A linguistic study based on Shakira's Rabiosa (De Souza-Tamburini and Dos Santos-de-Jesus, n.d.) reveals this song as a language-classroom tool to learn Spanish in Brazil, where the students have to grind down the metaphors in the song to elucidate their meaning so that they absorb the way some specific expressions are said in Colombian Spanish. As the authors of the article explain, a variety of feelings are manifested through wild instincts (De Souza-Tamburini and Dos Santos-de-Jesus, n.d.). Taking as an example the title of the song, Rabiosa, when the singer sings that she is rabiosa, it does not literally mean that she is “ill with rabies”. In Colombian Spanish it connotes sexuality, in this case, that she is strongly sexually aroused.

Lehtonen (2005) deals with music and its lyrics from a different perspective. Her analysis was related to the use of metaphors and music as a medical treatment since the lyrics of the song, specifically metaphors, evoke the most meaningful life experiences of patients in their past lives. The author uses the example of Simon and Garfunkel´s song Bridge over Troubled Water to explain the understanding of the strongest archetypal metaphors of sadness according to Jung’s treaty in 1978. According to Lehtonen (2005), the title reflects the image of “looking sad staring down at a flowing river”. Bob Dylan was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2016 because of his extraordinary poetic expressions in the American song tradition. Harmon’s (2012) study is based on a “compare and contrast” exercise on two artists: a songwriter and singer, Bob Dylan, and the Fifties American stand-up comedian, social critic and satirist Lenny Bruce. Harmon uses scales of definition and contrast between them, drawing conclusions on the reasons why one is highly considered in the media and society and the other one was forgotten in the sands of time. She says about Dylan “And if intercepted by another human being, the language in both poems and songs is often so full of metaphor and imagery that its meaning is veiled and subject to an infinite number of interpretations” (Harmon 2012, p. 1299). Creativity plays an important role in the poetic elaboration of the lyrics. As individuals, we are sometimes more creative than others in the way we express our daily events, actions, activities, or emotions.

Our study focuses on highlighting thoughts, beliefs and perspectives in life that our youth, main consumers of these commercial hits, are frequently exposed to. The results of this analysis will evidence the presence of metaphors in the contemporary commercial songs, corroborating that metaphors are pervasive in everyday life (Lakoff and Johnson 1980).

Our research questions are the following:

1. What are the most frequent topics mentioned in the songs that our youngsters listened to?

2. What values are associated with the metaphorical expressions of these songs?

3. What ideas, ideals and beliefs are our youngsters exposed to?

4. What discourse mapping can be outlined from this analysis?

In the present study, we aim at analysing the metaphors of the most-listened-to songs of the present day from two Spanish musical lists.

1.1. Materials and method

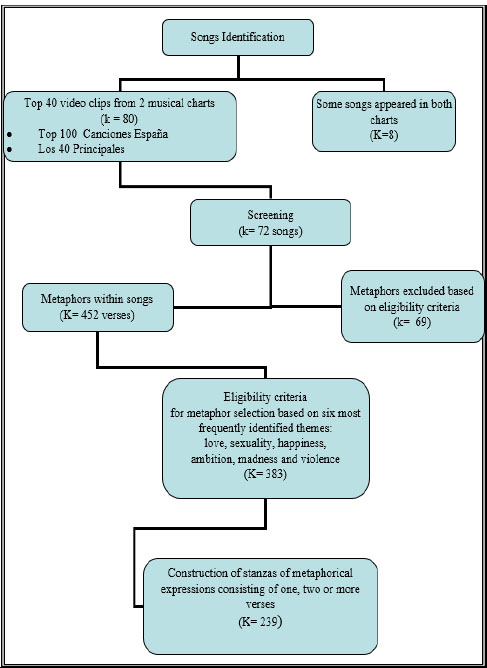

The songs analysed here were selected from two Spanish music charts following the top 40 most-listened-to songs chosen by the public. These songs come from five well-defined countries such as: Spain, United Kingdom, United States, and some well-located geographical areas in Latin America like Colombia and Puerto Rico, with two exceptions: one from Canada and another from France, both sung in English. The lyrics of these musical compositions are available online for free. The nationality of the singers was needed to know the point of origin of the songs, what may help connect the lyrics with their culture and progressively map out the guidelines of their inspiration. The songs are written in English or Spanish, the only two languages considered in this study. As explained by Manabe (2006), only in recent years have linguists begun to explore this forgotten field of contemporary songs based on one particular artist at the time. To our knowledge, fewer if not none have studied metaphors in 21st century’s songs as a whole. This study seeks to analyse the metaphorical component of the most popular contemporary songs in Spain (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Data collection and analysis protocol flowchart

Metaphors have been classified according to the topic they were addressing. Lakoff and Johnson’s (1980) own classification of metaphorical expressions has been considered to identify a specific linguistic expression as metaphoric. As regards the audience, adolescents and young adults are the ones who generally listen to Top 100 Canciones España and to Los 40 Principales. 452 metaphorical expressions have been extracted out of 72 songs (40 from each music chart equals 80 minus 8 repeated songs makes 72) which were included in the listings of two Spanish musical lists. 69 of those metaphors were excluded since they were addressing other issues regarding life itself such as: racism, prostitution, self-esteem or egotism, to set some examples; however, none of these issues were recurrent enough to be introduced as themes in this paper. The remaining metaphors 383 were then constructed into stanzas, that is grouping several verses belonging together to make sense of what the song is about; redundant lines were taken out, leaving a final figure of 239 metaphors which were analysed as they fitted into the most frequent topics.

1.2. Data analysis

Focusing on the metaphors framed by Lakoff and Johnson (1980), our initial identification of metaphors threw back 452 metaphorical expressions analysed under, for instance, the orientational or ontological frame, which helped to clarify the meaning, values, ideas, ideals and beliefs included in the 72 songs taken under scrutiny. For the 6 themes chosen and the 15 subtopics identified, one sample in English and one in Spanish were chosen. There are two exceptions: one lies in the category of fighting love where two examples in Spanish have been selected since the only example in English is from a song already used in this research, and another in the category of generic violence with no examples in Spanish. There are also 4 extra metaphorical expressions added for discourse analysis comparison and 5 extra samples drawn to represent the metaphorical density with original lines. These 38 main examples portray the songwriters’ background, fostering compositions depicting social issues by means of song/discourse charged with emotions where “a metaphor acts like a frame which is a discursive device” (Montagut and Moragas-Fernández 2020, p. 71).

2. Results

The high number of metaphorical expressions identified in songs confirms the pervasive use of metaphors in music just as much as in everyday life discourse. The analysis of the metaphorical density (MD = No. of metaphors x100 / Total No. of words) of commercial hits revealed that songs can be separated into three different groups: 1.4% of the songs included 6-8 metaphors, 34.8% contained 3-5 metaphors while 63.8% of them had 1-2 metaphors per song.

It is significant nonetheless to point out that in the group with the highest metaphorical density we find only one song with a score of 8.24, composed by Pablo Alborán titled Tabú and interpreted by Pablo Alborán and Ava Max: Si no queda amor Dime qué siento entre el pecho y las alas which stands for “If no love is left Tell me what I feel between my chest and my wings”. Belonging to the middle group we selected, as examples, the following two metaphorical expressions: Got me takin’ a step on the wild side Cuttin’ all ties from Come Thru by Summer Walker, and Sexo, ya ves, Maneja los tiempos Que la vida es solo un momento Yo no soy el malo en tu cuento meaning “Sex, you see, manages time Life is just one moment I’m not the baddy of your story” from Dosis by ChocQuibTown, Divicio & Reik. Finally, the majority of songs are constructed with a low metaphorical density such as: Though it took some time to survive you I'm better on the other side from Don´t start now by Dua Lipa, and Dime dónde irán los sueños que me quedan Si no queda más espacio en mi cabeza “Tell me where the dreams that I’ve got left will go since I have no more room left in my head” from Universo by Blas Cantó.

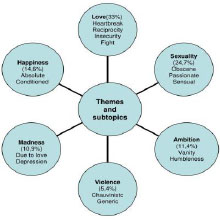

The thematic analysis of metaphors allowed the grouping of the identified 239 metaphors into the following topics: love, sexuality, happiness, ambition, madness and violence (see Table 1).

Table 1: Thematic analysis of metaphors in commercial hits (n= 239)

Topics |

Frequency |

Examples |

Love |

33% |

But when we kiss, I feel a jump in my Heart |

Sexuality |

24.7% |

You set the rain on fire I wish the lows were higher |

Happiness |

14.6% |

Strawberry lipstick state of mind I get so lost inside your eyes |

Ambition |

11.4% |

Chasing shadows one by one Doesn't matter where she's from Someone's daughter, someone's love 'Cause she's a diamond in a sea of pearls When are we gonna learn that we can change the world? |

Madness |

10.9% |

Take me down, To the bottom of the deep To your heartbeat Losing my grip Starting to slip |

Violence |

5.4% |

I’m armed to the teeth |

The analysis of these 6 recurrent topics revealed the existence of 15 subclasses that help to map this type of discourse: love was identified with heartbreak, reciprocity, insecurity and fight; sexuality was divided into obscene, passionate and sensual; happiness into absolute and conditioned; ambition into vanity and humbleness; madness into a condition due to love and depression; and violence into chauvinistic and generic. The examples chosen, 29 altogether, plus the 5 seen above regarding metaphorical density, and 4 extra for comparison, make a total of 38 metaphorical expressions selected due to their creativity (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Thematic analysis of metaphors found in commercial hits

2.1. Love

Love is an important emotion for us all, songwriters included (Ngamjitwongsakul, 2005). The most frequent metaphors of our sample spoke about love (33%) but as Bauman (2001) stated “we all know what love is - until we try to say it loud and clear” (p. 167). This reflects the way love is referred to in these commercial songs. Love is identified with heartbreak, reciprocity, fight and insecurity (see Table 2.1).

Table 2.1. Metaphors on love n= 79 metaphors; 33% of all metaphors found

Heartbreak n= 46 |

58.2 % of metaphors on love |

Reciprocity n= 18 |

22.8 % of metaphors on love |

Fight n= 8 |

10.1 % of metaphors on love |

Insecurity n= 7 |

8.8 % of metaphors on love |

Arias Patiño (n.d) mentions the “culture of lovers duel” and stated that love is frequently channelled through heartbreak-love stories. This is also the case in our corpus. Heartbreak songs are the most prolific ones, getting the highest rank of our classification (58.2% of all the love metaphors). The first example selected is from the song We Tried, We Tried by Ama Lou: Two became one But the foundation was weak and when it cracked it couldn't be fixed; this metaphorical sample is considered common or conceptual, perhaps hardly elaborated, comparing love and heartbreak with a construction building. The second example is in Spanish by Aitana, Cali & El Dandee, whose title is a simple + sign; this metaphor is more innovative, seeking originality: Entregarlo todo y quedarme con cero Por sumarle aniversarios a un amor que siempre será pasajero, which means “to give everything away and be left with nothing; all for adding anniversaries to a passing love”.

Examples:

Heartbreak58.2%

Example 1: Two became one, but the foundation was weak and when it cracked it couldn't be fixed (Ama Lou, We Tried, We Tried).

Example 2: Entregarlo todo y quedarme con cero Por sumarle aniversarios a un amor Que siempre será pasajero (Aitana, Cali y el Dandee, +).

Reciprocal love drops to a 22.8% in the list of love metaphors. Two examples are extracted from the list to reflect on the elaboration from the artists so metaphorically inspired: And life is moving so fast, I feel like everything's changing. But when we kiss, I feel a jump in my heart. The same feeling that I felt from the start from Chills by Why Don't We, and Cayó la noche y vimos las estrellas Y se alinearon los planetas pa´robarte el corazón from Robarte el corazón by Ana Guerra and Bombai, which stands for “the night fell and we saw the stars and the planets got aligned to steal your heart”.

Examples:

Reciprocity22.8%

Example 3: And life is moving so fast,I feel like everything's changing. But when we kiss, I feel a jump in my heart. The same feeling that I felt from the start (Why Don't We, Chills).

Example 4: Cayó la noche y vimos las estrellas Y se alinearon los planetas pa' robarte el corazón (Bombai & Ana Guerra, Robarte el corazón).

Love as a fight represents the 10.1% of our sample, while 8.8% shows love as insecurity. Love as fight is hardly elaborated and the only examples found are in Spanish: Sigues jugando con fuego Qué mala suerte para ti Ya no me voy Me quedo, meaning “You keep playing with fire Bad luck I’m not leaving anymore I'm staying” from Me quedo by Aitana and Lola Indigo. Also, the following example has been extracted from the song Vete by Bad Bunny: Así que vete lejos, dile al diablo que te envíe el pin, which means “go away, tell the devil to give you the pin number”. An example of insecurity would be evident in: She tried it, wore the mask, to put on a face but her feelings show from She by Hayley Kiyoko; and also the well-elaborated metaphor: Me muero Como aquel soldadito de hierro Que aguanta de pie en la batalla Con miedo, temblando, dispara, which stands for “I’m dying like that little iron soldier who endures standing in battle; frightened, shaky, he fires”. This war metaphor takes all the confidence out of the protagonist of this love song leaving just insecurity, by Nil Moliner and Dani Fernández in Soldadito de hierro.

Examples:

Fight10.1%

Example 5: Sigues jugando con fuego Qué mala suerte para ti Ya no me voy Me quedo (Aitana and Lola Indigo, Me quedo).

Example 6: Así que vete lejos, dile al diablo que te envíe el pin (Bad Bunny, Vete).

Insecurity8.8%

Example 7: She tried it, wore the mask, to put on a face but her feelings show (Hayley Kiyoko, She).

Example 8: Me muero Como aquel soldadito de hierro Que aguanta de pie en la batalla Con miedo, temblando, dispara (Nil Moliner and Dani Fernández, Soldadito de hierro).

2.2. Sexuality

The next theme to be examined is sexuality with a figure of 24.7% out of the total of 239 metaphorical expressions reviewed. Within this source domain, the subclass perceived as most prolific is obscene sexuality with a 47.5%. The reason why this category is framed as obscene is highlighted by the examples chosen. The metaphors taken from the songs are sexually provocative and even socially controversial with plain, simple and very basic verses, being pretty graphic and hardly support the semantics with any worthy elaboration; instead, the songs use the slang spoken on the streets. Nonetheless, a couple of examples have been detached from the rest according to their creativity, even though they are quite disdainful. In: Dice que le encanta mi producto Que la pongo a chorrear como un conducto by Leo Bash, Darell & Bryant Myers from the song La uni, which means “she says she loves my product, that I make her drip like a conduit” and I pop a perc and get to it Fucking that bitch, she nudie Double the cup for the fluid by Gnar & Germ from Perc 300 are very graphic examples of obscenity, but at the same time they are well elaborated compared to the simplicity of the following three different compositions. Está dura y abusa “she is hard and abuses'' by Nicky Minaj & Karol G in Tusa ; Llevo tiempo dándole “I’ve been giving it to her for a while” by Leo Bash, Darell & Bryant Myers from La uni; Perreamos hasta que tú ya no aguantes that refers to “doing it doggy-style ‘till you’re knackered” by J.Balvin found in Morado (see Table 2.2).

Table 2.2 Metaphors on sexuality n= 59 metaphors; 24.7% of all metaphors found

Obscene n= 28 |

47.5 % of metaphors on sexuality |

Passionate n= 26 |

44 % of metaphors on sexuality |

Sensual n= 5 |

8.5 % of metaphors on love |

Examples:

Obscene47.5%

Example 1: I pop a perc and get to it Fucking that bitch, she nudie Double the cup for the fluid (Gnar & Germ, Perc 300).

Example 2: Dice que le encanta mi producto Que la pongo a chorrear como un conducto (Leo Bash, Darrell & Bryant Myers, La uni).

Close in proximity in the ranking is passionate sexuality with a figure of 11% of all the metaphors found in this category. The two metaphorical expressions chosen, are well elaborated, and are the following: You set the rain on fire I wish the lows were higher by Ava Max in Torn, and Y te vienes y te vas, me subes al cielo Me muerdes la boca y en caída libre quiero by Vanesa Martín from Caída Libre which stands for “You come and go, You raise me to heaven You bite my mouth and I am free falling”.

Examples:

Passionate44%

Example 3: You set the rain on fire. I wish the lows were higher (Ava Max, Torn).

Example 4: Y te vienes y te vas, me subes al cielo Me muerdes la boca y en caída libre quiero (Vanesa Martín, Caída libre).

The difference between the previous sections and sensual sexuality does not only lie on the percentage with a scarce 8.5% but also on the high poetic elaboration of both examples. The first one is very well elaborated; sexual intercourse becomes poetry in Ed Sheeran's handwriting in South of the Border: I won't stop until the angels sing Jump in that water, be free Come south of the border with me, where he exemplifies Lakoff and Johnson´s (1980) “Love is a journey” extraordinarily. Then, we have Cuento las horas Para mirarnos bajo las olas Siento el momento De estar a tu lado y bailarlo lento, meaning “I count the hours to look at each other under the waves I feel the moment to be by your side and dance slowly” an example charged with sexual emotions and full of creativity interpreted by Ana Guerra and Bombai in Robarte el corazón.

Examples:

Sensual8.5%

Example 5: I won't stop until the angels sing Jump in that water, be free Come south of the border with me(Ed Sheeran & Camila Cabello, South of the Border)

Example 6: Cuento las horas Para mirarnos bajo las olas Siento el momento De estar a tu lado y bailarlo lento (Bombai & Ana Guerra, Robarte el corazón).

2.3. Happiness

This metaphoric discourse analysis would not be complete without considering happiness as one of the major factors in human identity. Humans base their sense of being in doing the things that make them happy; whether it is due to love, power, money, hope or, enjoyment, in other words, the engine that allows us to move forward (Myers 2000); making an endless list of characteristics that make life worth-living (Seligman 2002). Thus, happiness becomes the paradoxical object of desire (Nettle 2005). Happiness is pondered with 14.6% out of the total of 239 metaphorical expressions found in the commercial hits. Two types of happiness can be observed: absolute happiness (54%) and conditioned happiness (46%) (see Table 2.3).

Table 2.3 Metaphors on happiness n= 35 metaphors; 14.6% of all metaphors found

Absolute n= 19 |

54% of metaphors on happiness |

Conditioned n= 16 |

46% of metaphors on happiness |

Examples:

Absolute54%

Example 1: Walk in your rainbow paradise Strawberry lipstick state of mind I get so lost inside your eyes (Harry Styles, Adore you).

Example 2: Hay una estrella en tu interior Ya sé que no la puedes ver Hay tanta luz que se apagó Ya sé que tu dolor se fue (Manuel Carrasco, No dejes de soñar).

Conditioned46%

Example 3: I can't see clearly when you're gone I said, ooh, I'm blinded by the light (The Weekend, Blinding Lights).

Example 4: El deseo de vivir es lo que me está matando (Amaral, Nuestro tiempo).

Absolute happiness could be described as a temporary and elusive moment in somebody’s life when you see yourself at the top of your game being extremely difficult to keep up permanently, even though you do not realize this state of mind is just passing because there will always be worries that bring you back to earth. Thus, the two examples chosen that determine the summit of this powerful emotion, are: Walk in your rainbow paradise Strawberry lipstick state of mind I get so lost inside your eyes found in Adore You by Harry Styles; this stands for absolute happiness due to infinite love felt towards the object of desire; and Hay una estrella en tu interior Ya sé que no la puedes ver Hay tanta luz que se apagó Ya sé que tu dolor se fue which means “There is a star inside of you I know you can't see it There is so much light that it's extinguished I Know that your pain is gone” by Manuel Carrasco in No dejes de soñar; This sample is somewhat different to the former one, detecting absolute happiness as a consequence of pain being gone. Both examples are creative, innovative, and well elaborated.

On the other hand, conditioned happiness can be observed in: I can't see clearly when you're gone I said, Ooh I'm blinded by the lights by The Weekend in Blinding Lights being somewhat elaborated; this is clearly love affecting the psychological well-being of the individual (Coskun 2017), that affects a person when exposed to it; exactly the same effect is explained in: El deseo de vivir es lo que me está matando “The wish to live is what's killing me” by Amaral in Nuestro tiempo, being somewhat elaborated. We perceive once again love causing emotional damage when the lyrics are read in full.

2.4. Ambition

Ambition covers 11.4% of the metaphorical expressions identified. It is one of the main issues to attain happiness. There is, however, a distinction which points out to the way people state their inner self with regards to how to express that ambition, whether vain ambition or humble ambition (see Table 2.4).

Table 2.4 Metaphors on ambition n= 27 metaphors; 11.4% of all metaphors found

Vanity n= 19 |

70% of metaphors on ambition |

Humbleness n= 8 |

30% of metaphors on ambition |

Examples:

Vanity70%

Example 1: I can make it rain like no matter what's the weather (Lil Uzi Vert, Futzal Shuffle 2020).

Example 2: Los dejo ciego' con la vibra que me alumbra (J. Balvin & The Black Eyed Peas, Ritmo).

Humbleness30%

Example 3: She's on the same side Chasing shadows one by one Doesn't matter where she's from Someone's daughter, someone's love ´Cause she's a diamond in a sea of pearls (Echosmith, Diamonds).

Example 4: Me conocen por culpa del aire Me conocen los que hablan de ti Me conocen las guapas del baile Y los bares que cierran Madrid (Pablo López, Mama no).

The inference to vanity ambition (70%) is stated in the next two examples: I can make it rain like no matter what's the weather (facts) by Lil Uzi Vert in Futzal Shuffle 2020 where simplicity is the common status, and Los dejo ciego' con la vibra que me alumbra “My aura blinds people” by J Balvin & The Black Eyed Peas in the song Ritmo, is well elaborated, with high achievement in creativity, in spite of being probably slang in the singers´ place of origin.

Contrary to the above, we find humble ambition (30%) in: She's on the same side Chasing shadows one by one Doesn't matter where she's from Someone's daughter, someone's love ´Cause she's a diamond in a sea of pearls When are we gonna learn that we can change the world? by Echosmith in Diamonds being both, common in the metaphors used but also well elaborated, since even after reading the whole lyrics of the song several times, it takes time to realize what the authors talk about here, which is about empowering women, in other words feminism (Areerasada and Tapinta 2015; Vaitonyté and Korostenskiené 2015); women finding themselves being sick and tired of waiting in a passive mode for things to go their way. The protagonist of this song decides to take her chances and experience life for herself in a manly world with a very humble but determined way. The Spanish metaphorical model is again well elaborated: Me conocen por culpa del aire Me conocen los que hablan de ti Me conocen las guapas del baile Y los bares que cierran Madrid “I'm known because of the air I'm known by those who speak of you I'm known by the pretty girls of the prom and the bars that enclose Madrid” by Pablo López in Mama no.

2.5. Madness

The description of metaphors with respect to madness (10.9%) is divided into madness due to love and depression. Low self-efficacy and low self-esteem can lead to depression (Erozkan et al., 2016) (see Table 2.5).

Table 2.5 Metaphors on madness n= 26 metaphors; 10.9% of all metaphors found

Due to love n= 15 |

58 % of metaphors on madness |

Depression n= 11 |

42 % of metaphors on madness |

Examples:

Due to love58 %

Example 1: Take me down To the bottom of the deep To your heartbeat Losing my grip Starting to slip (The Trash Mermaids, Scarlett Blu).

Example 2: Y no sé, tú eras siempre la pistola y yo la bala No sé, te encanta jugar con fuego y ya hay mil llamas (Beret, Si por mí fuera).

Depression42 %

Example 3: When I open up and give my trust, They find a way to break it down Tear me up inside, and you break me down (Trevor Daniel, Falling).

Example 4: Casi vive siempre destemplado y a la espera de algún movimiento inesperado Es el epitafio más común en las esquelas De aquellos que nunca lo intentaron (Melendi, Casi).

In this section, Madness due to love metaphors (58%), an extra sample has been selected to exemplify with the next lines how the adrenaline rushing through the veins can almost be noticed when the object of your affections is nearby: Si me dices que sí, sí (Que sí) Me muero y me desmuero solo por ti, “If you say yes, I´ll die and I´ll undie just for you” from Tutu by Camilo and Pedro Capó. It is hardly elaborated but very meaningful.

Proceeding with the analysis, the two set of verses chosen to describe this source domain are: Take me down, To the bottom of the deep To your heartbeat Losing my grip Starting to slip from Scarlett Blu by The Trash Mermaids; and: Y no sé, tú eras siempre la pistola y yo la bala No sé, te encanta jugar con fuego y ya hay mil llamas “And I don’t know, You were always the gun and I the bullet I don’t know You love playing with fire and there are already a thousand flames” from Si por mí fuera by Beret. Both are well elaborated and represent madness due to love, people becoming vulnerable and permissive.

The depression metaphors mainly refer to other than love, like self-esteem and confidence. With: When I open up and give my trust They find a way to break it down Tear me up inside, and you break me down, by Trevor Daniel from Falling, where the singer expresses his state of mind, which is depressive. It is not a creative metaphor but quite common. The other example, Casi vive siempre destemplado y a la espera De algún movimiento inesperado Es el epitafio más común en las esquelas De aquellos que nunca lo intentaron “Almost lives always feverish and awaiting an unexpected move It is the most common epitaph in obituaries From those who never tried” from Casi by Melendi, which gives the impression of desperation, of living a life full of lies without any positive achievement, turning the lack of action into a habitual modus operandi, but at the same time understanding the cowardice and therefore falling into depression for not being able to even try or act upon one’s needs. This one is well elaborated with the vivid personification of casi.

2.6. Violence

Last category is violence (5.4%) which is not a common subject in contemporary commercial songs. We have only two subclasses: chauvinistic violence and generic violence with 69% and 31% respectively; noticing that the violence addressed to women is higher (see Table 2.6).

Table 2.6 Metaphors on violence n= 13 metaphors; 5.4% of all metaphors found

Chauvinistic n= 9 |

69% of metaphors on violence |

Generic n= 4 |

31% of metaphors on violence |

Examples:

Chauvinistic69%

Example 1: She tried to show out in public, I cut the bitch off like it's nothin' (Moneybagg Yo, U Played).

Example 2: Si me dejas, yo soy la aguja Y tú mi muñeca vudú-dú (Camilo & Pedro Capó, Tutú).

Generic31%

Example 3: Round after round after round, I'm gettin' loaded Commando with extra clips, I got ammo for all the hecklers I'm armed to the teeth (Eminem, Darkness).

Regarding chauvinistic violence, the few and hardly elaborated metaphors are crude and insulting for women, whether physical or psychological violence: She tried to show out in public, I cut the bitch off like it's nothin' example extracted from U Played by Moneybagg Yo. What is recurrent amongst the examples, however, is the spiteful noun “bitch” charged with negative connotations about women, to subjugate and to undervalue them. The softest and somewhat elaborated instance is the one and only example in Spanish: Si me dejas, yo soy la aguja Y tú mi muñeca vudú “ If you leave me, I’m the needle and you’re my voodoo doll” from Tutu by Camilo and Pedro Capó.

Finally, Eminem is the star of our generic violence section with his song Darkness filled with common war metaphors which makes us think that perhaps the verses were more literal than intended. An example of this is the following: Round after round after round, I'm gettin' loaded Commando with extra clips, I got ammo for all the hecklers I'm armed to the teeth. These metaphors are common or conceptual. There are no examples in Spanish in this section.

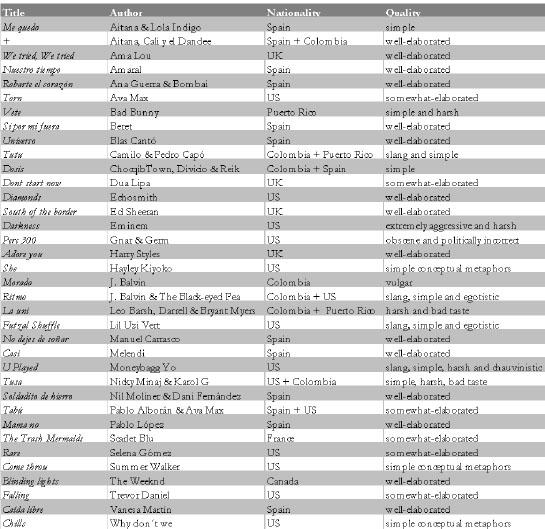

2.7. Culture-bound metaphors, countries and quality

The following table reflects the songs used in this study together with the singers, their nationality and quality of the metaphorical expressions written in the commercial hits that have been previously analysed. The countries of origin of the authors determine the culture-bound metaphors that they use to express their emotions, feelings, ideas, ideals and beliefs. It is the background that surrounds them that gives the context for inspiration to pursue the art of metaphor production in the music industry.

Table 2.7 Culture-bound metaphors, countries and quality

Table 2.7 shows examples of different types of metaphorical compositions according to their quality. It is specified if they are well elaborated, simple conceptual metaphors or harsh and blunt. The difference portrays a distinct perspective of life on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean.

3. Discussion

Our main objective has been to verify if songs contain metaphors in the first place, as we hypothesised. In the second place, we have stated that metaphors present in the commercial hits studied can be thoroughly thought of, or bluntly composed with contempt. The pervasiveness of metaphorical compositions in contemporary songs has been highlighted and the added values that a metaphor impregnates an expression with has been strengthened.

We built up a corpus of 452 metaphorical expressions out of two Spanish music lists in a random week of 2020 to perceive the intrusion of metaphors in the contemporary songs. The great majority of these metaphors categorize as one of the six themes: love, sexuality, happiness, ambition, madness and violence. These themes were grouped into 15 subtopics which were analysed, so that a clear divergence between themes was considered when determining the artists’ motives of their creative compositions. Metaphors are observed as strong and powerful tools in these contemporary songs. Only 69 metaphors did not account for any of the mentioned topics but for other issues in life, without a recurrence: racism, egotism, general insecurity, amongst others.

A distinct differentiation between the songs within the two musical charts selected was soon noticed. The values extracted from the metaphors of European compositions appealed much subtler, always more temperate. These songs, some more dramatic than others, praise the beauty of living, with a calmer and feet-on-the-ground aura, than those of the Americas, whether United States or the two Latin American countries mentioned, whose songs are disturbing, being almost always on the line of the non-politically correct side. Those American metaphorical expressions (whether from the North or South) are used to portray a set of values diverted from graciousness. Their line of thinking drifts in a devalued, eccentric, and in some cases insulting turn where obscene sexuality takes it all, whose source domain seems to be the streets where the narrative discourse fosters cruelty, chauvinism, lack of empathy and violence. There are exceptions to this rule: one of which is The Weeknd, author of Blinding Lights, Canadian, and Selena Gomez’s Rare: Saw us getting older Burning Toast in the toaster.

These metaphorical constructions are associated with ideas, ideals and beliefs of our society. Frequently, women are called “bitch” and sex is taken very lightly. Also, some songs depict great doses of self-esteem and egotism exemplified in the metaphor los dejo ciegos con la vibra que me alumbra “my aura blinds everyone”. Male singers often refer to this metaphor as an influencing factor intertwined with happiness. The immediate consequence of this way of thinking is proactiveness as the lyrics of their songs denote, ejecting them forward and upward. However, in opposition to the above, we also find metaphors that indicate depression and aggressiveness because of heartbreak love-stories, among other reasons. This creates a sort of pattern to repeat as a new norm “to be cool”. The use of this language entails a lack of sensitivity that our youngsters are exposed to. This analysis also observes a tendency, mostly regarding American female singers (whereas from North America or Latin America), where this aggressive manly behaviour has been depicted. Lyrics but also video clips show an aggressive manner of telling the audience that they are “cool” and promote, therefore, the copycat modus operandi.

However, as seen in this research, songs not enriched with elaborated metaphors can be equally successful and be present in international radio stations thanks to a catchy rhythm, even though their musical compositions lack instruction and knowledge. Regarding the culture-bound metaphors analysed in this study, there is also a need to consider the closeness of the two sides of the Atlantic Ocean due to a common historical background between Spain and Latin America. This is portrayed in the likings and music taste of today’s Spanish audience. The message (the lyrics of songs) created in one culture is listened to in another, creating a sort of intercultural exchange. But this message is interpreted blindly. Blindly because the perception of expressions that are culture-bound could induce error in understanding. For example, Shakira's Rabiosa means being “sexually aroused” in Colombia but “furiously angry” in Spain.

Our analysis shows that pervasiveness of metaphors is present in commercial hits as well. Our discourse analysis focuses on the contextual meaning of language, and it was interesting to describe these metaphors from the point of view of poetic elaboration and creativity, but above all from the emotional perspective. By studying the metaphors of these songs, we detached the emotional charge and context, therefore the background, of the song-makers, and their sense of life.

4. Conclusion

In this article, we have conducted a descriptive discourse analysis based on metaphors in contemporary commercial songs and values and beliefs that are transmitted by the song-makers to our youngsters. This approach helps us draw the perspective of life on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. Nevertheless, cautious interpretation of the findings must be exercised. The identification of a specific discourse mapping indicates that life is certainly viewed harsher in the new continent, whereas in contrast in Europe, metaphors underlie the projections of much more promising values of life, according to the two Spanish musical charts of commercial rhythms selected. The implications of these findings may rely on song-writers educational context. All in all, human beings are essentially alike, and metaphorical creativity can be outlined even in those compositions considered blunt. Songwriters seem to feel the linguistic need of inventing new expressions with which to vehemently transmit in just a few words a feeling or to express an action. Would songwriters write about love, sex and women so disdainfully if they had received a more valuable education when children? Would songwriters think and talk about violence if they had not seen such violence portrayed in their society since childhood? Further research is needed to answer these questions and to observe the impact of these metaphors on youngsters who very frequently listen to these songs.

Finally, in order to develop a further view of metaphors in contemporary songs, the scope of study should be expanded to the visual and gesturing metaphorical components of video-clips. This will allow us to draw conclusions on the social implications of the nature of both, the artists and their audience, as much as the message transmitted and its influence on the young people’s behaviour.

To sum up, this study contributes to evidence that metaphors are not only pervasive in everyday conversations but also in commercial hits. They are the way singers and songwriters have to fully express their thinking and feelings, that is to say, their emotions.

Funding

This study has been supported by the R+D project “Musical aptitude, reading fluency and intercultural literacy of European university students” (FFI2016-75452-R, Spain, Ministerio de Economía, Industria y Competitividad).

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding authors.

5. References

Areerasada, M. & Tapinta, P. (2015). Feminism through Figurative Language in Contemporary American Songs of Leading Contemporary Feminist Music Icons. Suranaree J.Social Sciences, 9(2), pp. 1–21.

Arias-Patiño, H. (n.d.). Canción y duelo. La canción de amor dentro de una cultura del duelo analizada a través de la metáfora discursiva. Accessed 9th March 2020. https://cutt.ly/zhbfr5Z.

Bauman, Z. (2001). The Individualized Society. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Bywater, I. (1920). Aristotle on the art of poetry. New York: Oxford University Press. Accessed 17 April 2020. https://archive.org/details/aristotleonartofOOOOaris.

Caballero, R. (2014). Thinking, drawing and writing architecture through metaphor. Ibérica, 28, pp. 155–180.

Castaño, E. (2020). Discourse analysis as a tool for uncovering the lived experience of dementia: Metaphor framing and well-being in early-onset dementia narratives. Discourse and Communication, 14(2), pp. 115–132. Accessed 9 March 2020. https://doi:10.1177/150481319890385journals.sagepub.com/home/dcm.

Chen, E., Gibbs, R. W. & Okonski, L., (2020). Metaphor in multimodal creativity. In L. Hidalgo-Downing & B. Kraljevic-Mujic (Eds.), Performing Metaphoric Creativity across Modes and Contexts. Figurative Thought and Language, pp. 19–42. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Coskun, Y. (2017). Values within the context of postmodernity and their roles in happiness: a research on university students. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 5(12), pp. 2331–2340.

De Souza Tamburini, M. & Dos Santos de Jesús, T.A. (n.d.). Un estudio semántico de las metáforas lingüísticas en la canción Rabiosa, de Shakira. In: Universidade Federal do Maranhao (ed Ele-Usal), El Salvador.

Erozkan, A., Dogan, U. & Adiguzel, A. (2016). Self-efficacy, self-esteem, and subjective happiness of Teacher candidates at the pedagogical formation certificate program. Journal of Education and Training Studies, 4(8), pp. 72–82.

García-Olivares, A. (2007). Metáforas del saber popular (III): el amor en el tango. Acciones e Investigaciones Sociales, 23, pp. 139–179.

Harmon, L. (2012). Bob Dylan on Lennie Bruce: more of an outlaw than you ever were. Fordham Urban Law Journal, 38, pp. 1287–1303.

Hidalgo-Downing, L. (2020). Towards an integrated framework for the analysis of metaphor and creativity in discourse. In L. Hidalgo-Downing & B. Kraljevic-Mujic (Eds.), Performing Metaphoric Creativity across Modes and Contexts. Figurative Thought and Language, pp. 1–18. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Hidalgo-Downing, L. & Filardo-Llamas, L. (2020). Metaphor and creativity in lyrics and performances of three songs by U2. In L. Hidalgo-Downing & B. Kraljevic-Mujic (Eds.), Performing Metaphoric Creativity across Modes and Contexts. Figurative Thought and Language, pp. 71–96. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Illescas, J.E. (2015). La dictadura del videoclip: industria musical y sueños prefabricados. Intervención Cultural.

Kövecses, Z. (2010). A new look at metaphorical creativity in cognitive linguistics. Cognitive Linguistics, 21(4), pp. 655–689. Accessed 3 October 2019. https://doi.org/10.1515/cogl.2010.021.

Lakoff, G. & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors we live by. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Lehtonen, K. (2005). Music as a possibility of chance – healing metaphors in music. Music Therapy Today, 6(3), pp. 356–374.

Manabe, N. (2006). Lovers and Rulers, the Real and the Surreal: Harmonic Metaphors in Silvio Rodríguez´s Songs. Revista Transcultural de Música, (10). Accessed 13 March 2020. http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=82201013.

Márquez-Reiter, R. & Hidalgo-Downing, R. (2020). Intercultural communication in a globalized world. In Handbook of Spanish Pragmatics, pp. 305–320. Routledge.

Musolff, A. (2012). The study of metaphor as part of critical discourse analysis. Critical Discourse Studies, 9 (3), pp. 301–310. Accessed 7 May 2020. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2012.688300.

Myers, D.G. (2000). The funds, friends, and faith of happy people. American Psychologist, 55, pp. 56– 67.

Ngamjitwongsakul, P. (2005). Love Metaphors in Modern Thai Songs. MANUSYA: Journal of Humanities, 8(2), pp. 14–29. Accessed 13 March 2020. https://doi.org/10.1163/26659077-00802002.

Nettle, D. (2005). Happiness: The Science Behind your Smile. New York: Oxford University Press.

Sal Paz, J.C. (2009). Acerca de la metáfora como recurso de creación léxica en el contexto digital. Algunas reflexiones. Tonos Digital, (18).

Sánchez-Vizcaíno, M.C. & Fonseca-Mora, M.C. (2019). Videoclip y emociones en el aprendizaje de Español como Lengua Extranjera. Círculo de Lingüística Aplicada a La Comunicación, 78, pp. 255–286.

Sánchez-Vizcaíno, M.C. & Fonseca-Mora, M.C. (2020). Mediación y pensamiento crítico en el aprendizaje de lenguas: el análisis de videoclips musicales. Revista de Estudios Socioeducativas, 8.

Seligman, M. (2002). Authentic happiness: Using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfilment. New York: Free Press.

Vaitonyté, J. & Korostenskiené, J. (2015). Feminine Imagery in Contemporary American Pop Songs: A contrastive Analysis. Sustainable Multilingualism, 6. Accessed 9 March 2020. http://dx.doi.org/10.7220/2335-2027.6.6.